Once you read a few Superman stories, it becomes clear how neurotic the character sometimes can be. For decades, he compulsively hid his identity from nearly everybody he knew and loved, sometimes going to absurd lengths (an issue by Otto Binder sticks out in my mind, one in which Jimmy somehow learns his identity and Superman spends a whole day convincing him that he’s insane so that he’ll dismiss it). He really cares what other people think, too, and a recurring scene is Superman flying around or hovering above Metropolis, listening to what people say about him. Superman actively wants to stand for something and to make us better, and that means doing things the hard way. If Batman had his powers, the world would change overnight. Batman doesn’t really care about making people better, just stopping crime and giving people who are already good a better world to live in. He wouldn’t care for national boundaries, or representing America or freedom, or convincing authorities, or collecting evidence. For Superman, inspiring and bettering people is more important than getting the job done easily, or even permanently. That’s Joe Kelly’s “What’s So Funny about Truth, Justice, and the American Way” (Action Comics 775) is about.

The premise of “What’s So Funny” is that four super-powered anti-heroes called the Elite spontaneously show up on the world scene.

They’re a thinly-veiled analog to the Authority: they’ve decided to take matters into their own hands and, without responsibility to any government, or anyone at all for that matter, to save the world. To them, that means doing away with supervillains once-and-for-all by killing them (and like the Authority, they’re led by a gruff, irreverent Brit and taken up residence in an inter-dimensional ship). A few pages before we meet them, we see the kind of carnage they leave in their wake:

Their powers are ill-defined, but quite extraordinary. This all occurred in the four minutes it took for Superman to arrive on the scene, and, in addition to the giant ape, who was attacking Libya, they killed two-thousand Libyan soldiers. In an early confrontation, they freeze Superman’s electrons and kill a team of villains before his eyes. But they don’t want to fight him; they want him to stay out of their way. As they say in their manifesto, “You asked for us, world. Now you got us. Be good, or we’ll blow your house with a fifty-megaton cold-seeking cluster bomb. Love us.”

And, as Superman sees as he flies around Metropolis, many people welcome the Elite. Sure, it’s easy to talk about “The Right Thing,” but what’s the point of putting guys like Szasz or the Joker into prison? What do you do about villains who don’t have any demands, but just want to blow up Tokyo? As another reporter tells Clark, “The world is sick and broken, Kent. People want someone to fix it.”

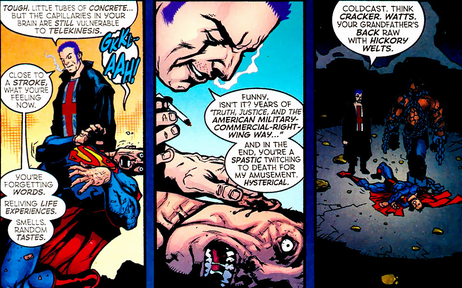

This is what drives Superman to challenging the Elite to a fight. Not their brutal, illegal methods and the fact that they are killing villains. What does it is that people are buying into their rhetoric and giving up on the idea of “The Right Thing,” giving up on Superman. So, he fights them on a moon of Jupiter. It’s been established that they are vastly more powerful than he is, and things look bleak at first when their leader gives him a super-stroke.

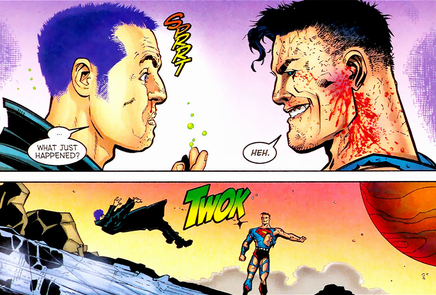

But, using cunning and speed, he separates them and beats the crap out of them. In fact, he convinces their leader, and the reader, that he’s killed them at first, and their leader is reduced to a sobbing heap. This is all televised, and Superman’s idea is to shock and revolt the world – to show how scary it is if we let our heroes cross the line and to keep the world from wanting this in our heroes.

I like this story, and it’s gratifying to see the Authority get their asses kicked by Superman. But it has a problem that stories like this often have. Superman argues that might doesn’t make right and the ends don’t justify the means, that principles and morals mean something. But how does he prove this? By being stronger than they are and beating them in a fight. So 1) Superman’s moral system is supposedly superior, but 2) that doesn’t matter because he can beat them at their own game. That’s really unsatisfying.

Where the Elite’s solution to villains and evil is to kill them, Superman’s solution is to put these guys in jail. Sure, they may get out and wreak some havoc, maybe even kill some innocent people, but then to fight them, beat them, and put them in jail again. His solution is to endure loss and to fight forever. He says as much on the last page of the story.

But this take is easy for a guy like Superman: he’s a Superhero, the greatest of the Superheroes. He has the luxury of fighting forever, and he doesn’t feel envy, greed, weakness, weariness, inferiority, or hunger the way we do. As the Elite’s leader tells him, he’ll never have to “try eatin’ yer own dog to survive, cause yer sister lost ‘er hands in a sweatshop.” If he doesn’t feel fear the way we do, what does his courage mean? What does it mean for him to show restraint and not kill when the stakes are in some ways so much less for him?

These are hard questions, and even if it is unsatisfying, “What’s So Funny“ does touch on them. When it looks like Superman has brutally killed the Elite one by one, certainly I was repulsed, and, like the audience he was trying to convince, I knew more than ever that this wasn’t what I want from my Superman. The point is that we may stumble and fall, make amoral choices that debase us, do things to protect ourselves and our loved ones at the cost of our souls. But Superman never will, and he has the luxury of doing this because he isn’t us and his world is different from our own. But why make him and his world more like us and ours instead of the other way around? Why should we warp in imitation of our base world the best our imagination has to offer? A consequence of this, however, is that this means we are required to admit that there are just some stories we simply can’t tell with Superman and that there are problems he simply can’t deal with.

Pingback: Superman: For the Animals « Fourth Age

Pingback: The Mighty « Fourth Age

Pingback: The Mighty | Fourth Age of Comics

> But this take is easy for a guy like Superman: he’s a

> Superhero, the greatest of the Superheroes. He has

> the luxury of fighting forever, and he doesn’t feel envy,

> greed, weakness, weariness, inferiority, or hunger the

> way we do.

This is a fair point, but I’d argue that Joe Kelly wasn’t saying that WE should be like Superman. Rather, he was saying that SUPERHEROES shouldn’t embrace the brutality and joy in savagery that the Authority heartily accept within themselves and their compatriots. Demigod heroes without rules are terrifying, and while as a superhero, Superman may be less effective in the short-term, even the Wildstorm titles showed how the Authority’s methods would inevitably lead to disaster: the Authority (and the Wildcats) terrified humanity with their displays of merciless force, resulting in humans attempting to create their own superhumans, which led to the destruction of the Earth and the Authority trying to be heroes in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

Well, I think an important component that that does not acknowledge is that the Authority – and this Authority pastiche – are not embracing savagery for savagery’s sake. The aim of the Authority and this analog is that they will cut through all the red tape, discard conventional morality, and do what needs to be done For the Greater Good – meaning among other things killing people who are too dangerous to live or saving the world from itself, even if the remedy is bloody or cruel. One of the critiques of conventional superheroes in the book is that they take these murderous villains and throw them into prison, letting them break out to murder all over again; because they are such moral, law-abiding members of the status quo, they are committed to a cycle that lets innocent people die. But Manchester Black says of himself and his team, “We’re human beings with the power to make a difference, doin’ what any normal person would, given the chance” – they are making the moral compromises that Superman has the luxury of not making, the compromises that (Manchester claims) you or I would or do make. Because Superman’s so super, he is pretty much fearless and capable of living in a world of eternal struggle. He’ll never have to be, as Manchester Black also says, so hungry that he has to eat his own dog. The Authority, however, and Manchester Black’s team are closer to “real” humans and willing to make those compromises. That is in fact why the public opinion in this comic turns towards them and away from Superman, and this is an important factor in his decision to fight Manchester Black’s team. Such compromises have close analogs in the “real” world, of course. A large segment of the American public lets government agencies violate their constitutional rights for the sake of fighting enemies felt to be so dangerous, conventional rules do not apply. A probably larger segment is willing to let the American government use either extraordinary rendition or its own extra-national prisons to torture or indefinitely confine foreign enemies who are felt to be so dangerous, interrogating them or letting them stand trial in America under American laws would be unacceptable. I think part of what Kelly is going for is that we make such moral compromises because we’re scared, we’re looking out for ourselves, and it seems like they will save us – they are in the name of the greater good. Unlike us, and unlike Manchester Black, Superman will not ever compromise those morals; and even though we will fail, that’s what we should aspire to – and that is what, as you say, we should have our heroes aspire to.

You forgot one (very important) point: Superman is not what he is because he was born in krypton. A major quality of kryptonian people is their lack of feelings. Superman is an orphan, and perhaps the nature factor allows him to be different from us. But nurture factor makes him at least 50% human.

It’s well known that his character is a fruit of his ‘earthling’ creation (where else would he learn about the ‘american way’?). He is, although, a symbol, something that allows us to be better. Like Captain America, on Marvel Universe.

In a minor scale is that same thing that makes Peter Parker forget his personal life and swing around in a web: he chooses to be in second plane. To be a hero. That’s what Gandhi, or Mandela, or Queen Elizabeth did: they turned in something more than a mere human by embracing an idea – and becoming a symbol of that idea.

Of course Superman is the best to do this. He takes our humanity into a higher level, ’cause he is the first one, the best. But don’t matter how super he is, he’s chosen to be a (super)man. Not a mere kryptonian.

u can’t force people to be good…

Reading your article I may have misunderstood you but disagreed with some of what I perceived as your opinions. First that the authoritys savagery is done for the benefit of man not self interest of the team. They demand be a better place, OR ELSE. But here lies a fundamental problem with teams like the authority, whose definition of better are they using? And what gives them the authority (no pun intended) to bully governments chosen by the people being governed into doing what the team wants? Superman feels a human life is precious and no one has a right to take it(action585). But while respecting life he also respects choice. Superman chooses to respect the authority of governments/people to govern themselves. While he may wish they were different he attempts this by leading by example not as a god/dictator forcing change. This is where might does not make right: in world view/opinion. You can’t change someone’s views with your fists but you can stop the immediate pain they causing, giving them the opportunity to change. This is why he stops killers and space threats but not government killing like capital punishment or abortion. And those he stops he places in the peoples hands to choose the punishment themselves. Their fate and the fate of the criminal is ultimately in the peoples hands not one super man. The eternal struggle is their doing not his. If the people really wished to end the treat permanently it is for them to sentence to death he would not stop their choice. But the blood would be on their hands not his. Thus the authority taking lives THEY deem forfeit is taking choices of people away from them and FORCING their morals as the objective right ie playing god of the world.

Second, In the fight with the elite you claim by beating them up he is showing 1) his moral system is supposedly superior, but 2) that doesn’t matter because he can beat them at their own game. I think this misses the big picture. He is not showing the elite he can beat them at their game, he is showing the PEOPLE this way is wrong. As you said, he goes around seeing people buying into the elites rhetoric, so the fight is for their benefit not the elites. He truly believes might doesn’t make right so he would never pound on someone until they followed his opinion like the elite. He is acting as an attorney giving his closing arguments but with a fight instead of a speech. Showing actions speak louder than words his actions scream to the people that an immoral superhuman dolling out their own brand of justice rather than letting the people decide punishment is a scary and dangerous thing.

lastly, superman is an immortal/invulnerable superhuman and so can afford to be uncompromising. This idea would be true if superman were anyone but superman. If he viewed the world selfishly he has nothing personally at stake. But this is where all the savior imagery of superman kicks in and why he is more human than average people. His powers give him a unique connection to humanity not separate him. Given supes powers for a few minutes lex luther was brought to tears to view the world as supes did; to see how connected we are, how short a human life is and how precious those moments are. (allstar supes 12). For this reason, every death and every pain of people Supes carries as his own. Every time someone eats their dog or loses their sisters hands affects him personally because he feels it with them, he knows they’re out there and believes with his power he had a chance to prevent it. For lack of a better phrase he truly believes with great power comes great responsibility. He doesn’t feel fear like us because our fear is so small(ourselves our families…etc) his fear is huge because he fears for us all as his family. So his power doesn’t remove him from humanity making him have less at stake from a continuing threat, quite the opposite his connection to all people means he has MORE at stake than anyone on the planet.

Thanks for the reply; it’s been a while since I wrote this or read this comic, but I’ll try to respond. You are right that the premise of the Authority is that they are the highest authority — beyond government, beyond reason, beyond compromise — and in that regard they operate beyond the agency or choice of the people they protect. But the insidious problem that Superman faces with the Elite is that the public agrees with them: they are given license by the people, who are sick of their weak/corrupt/merciful governments not sufficiently protecting them. They choose the Elite over Superman; the problem is not that the Elite are taking away agency from the people. The problem is that the people are wrong and need to be convinced otherwise.

Regarding your second point, Superman’s demonstration is, of course, indeed designed to show the people that they are wrong. But it bothers me that this entails using the very methods he rejects: he proves merciless force is wrong by being more capable of applying it than the Elite. If he weren’t more powerful than the Elite, he would still be right. But then he wouldn’t be able to prove it. As I said, superhero books routinely translate moral conflicts into physical ones, but it is a little disappointing that, in a book about how we shouldn’t and, in fact, in our heart of hearts don’t, privilege violence and intransigence over thoughtfulness and mercy, the conflict is still resolved by Superman beating the crap out of his opponents. Because then, the conclusion is problematic: yes, he convinced the public that they don’t want a Superman with Authority by showing them how revolting and debasing that would be, but he’s also shown them, and us, that he’s the biggest, most dangerous, most powerful badass around, and we had better not forget it. The latter is not the point he is trying to make to the public, but it is inextricably connected to his demonstration of the former.

Now, the display is meant to show the public, and us, that if Superman used the methods of the Elite, the methods they think they want, we feel frightened, revolted, and debased. You are absolutely right that Superman represents the best in us, is more human than us, and feels humanity’s pain more vividly than any one of us does. I get that, Grant Morrison gets that, and Joe Kelly certainly gets that. But maybe this story is simply too short, but I feel like in the story the public’s sense of this is never sufficiently treated — because their complaints are never sufficiently addressed. In that universe, being merciful, doing the right thing, and being humane does mean that good people will sometimes suffer and die when, e.g., a supervillain escapes from a justice system that was never designed to accommodate such types. Some people are legitimately upset about that price, because not only is not everyone invulnerable like Superman, not everyone is as humane. From a certain perspective, maybe Showing No Mercy to Assholes is also The Right Thing, and choosing to cede such authority to Superman might look very attractive. I find the idea that if the public simply saw Superman acting in such a way, they would be appalled and immediately reject that point of view because they actually love their mercy and humanity oh so much, they just didn’t know or lost track, too dismissive. Indeed, for a lot of people, a Superman with Authority is exactly the hero they’ve been waiting for—a real champion of truth, justice, and the American Way.

One of the best intertexts with this story is Kingdom Come, which poses a very similar scenario. There, the public’s favor likewise turns in the direction of a group of Cold Blooded, Take No Shit, Heroes with Authority, led by Magog, who was clearly inspired by the ultra-violent Rob Liefield type heroes of the 90’s. He challenges Superman to a fight to settle their difference of world views, and Superman declines. What would defeating Magog show? That he’s right because, while he always could have done the sort of stuff Magog does, he’s chosen not to? Does that mean if he couldn’t have beaten Magog, he’d be wrong? The point is, the public has made their choice. They’re wrong, and they do eventually come around, but, like us, they’ve been living in a hard world. In Kingdom Come, Superman may have been wrong to go into exile, but he’s right that superior force can’t prove moral superiority. His display in What’s So Funny is contingent on his superior force, and I don’t think it’s possible to separate that from the point he’s trying to make. Even if he has proved his point by giving them the Superman they think they want and showing them how horrible it would be, he did it by overpowering the champions of the contrary view.

Pingback: Review: Action Comics #978 – Cyber Cashola